Introduction

As the time for renewal of the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) mandate is only months away, there are reports of external pressure to change the mandate to make it more aggressive under Chapter VII or pack up. The United States (US) and Israel never wanted UNIFIL in its current form after the 2006 war. It was a larger political compulsion to deploy a mission comprising capable peacekeepers, including armed contingents from three developed nations from the West, but under Chapter VI. Despite UNIFIL’s mandate, which is in an assistance role to the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF), Israel always apportions the blame on UNIFIL for Hezbollah’s presence and its growing strength in South Lebanon. Hezbollah’s active part in the recent conflict vindicated Israel’s position on the continued utility of UNIFIL. The US and Israel have now indicated that the mandate of UNIFIL must be changed to Chapter VII to give the mission more teeth to clean up South Lebanon using all necessary means including using force. However, would authorising UNFIL to use force under Chapter VII help disarm Hezbollah completely? If the answer is ‘No’, what should be the UNIFIL’s structure and its approach to peacekeeping in South Lebanon. This article is an attempt to find answers to these questions.

The Context

As reported in a publication of Israel’s Institute for National Security Studies, Orna

Mizrahi and Moran Levanoni, two former Israel Defense Forces (IDF) officers, have

stated that since UNIFIL was expected to rein in Hezbollah, and it failed, it is time for

UNIFIL to either pack up or become more aggressive under Chapter VII. As the time

comes for the United Nations Security Council to renew UNIFIL’s mandate (UNSCR 1701), there is tension. According to Lebanon’s political analyst Ghasseb Mukhtar,

on the Lebanon Debate website, the US may oppose the renewal unless UNIFIL’s

mandate is changed to Chapter VII with more authority to enforce the resolution.

Both the US and Israel never wanted UNIFIL in its present-day form aftermath of the 2006 war. But global politics prevailed, and the mission’s present structure was accepted with reluctance. Israel, however, has never failed to criticise UNIFIL for its failure to implement the mandate. Now this is an opportunity to force UNIFIL to do its bidding or get rid of it to allow IDF unhindered movement in South Lebanon.

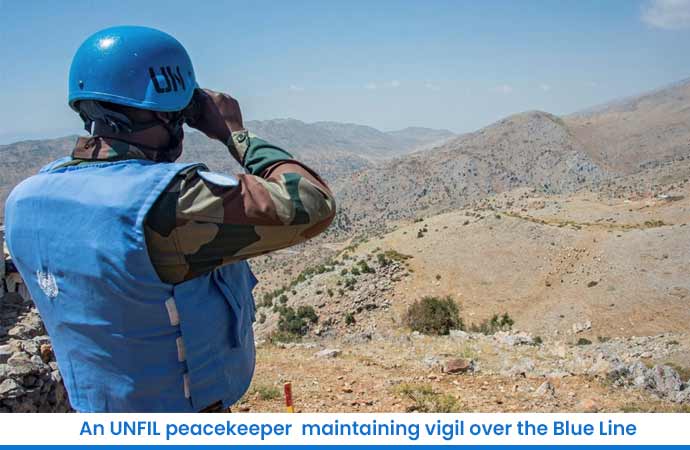

UNSCR 1701 mandates UNIFIL to assist the LAF to ensure security arrangements to prevent the resumption of hostilities, including the establishment between the Blue Line and the Litani River of an area free of any armed personnel, assets and weapons other than those of the Government of Lebanon and UNIFIL. However, paragraph 12 of the same resolution authorises UNIFIL to take all necessary action in areas of deployment of its forces and, as it deems it to be within its capabilities, to ensure that its area of operations is not utilised for hostile activities of any kind. The built-in ambiguity in the mandate leaves scope for different interpretations of the mandate and pronouncing judgment on UNIFIL. Supposing this ambiguity is removed from the mandate and UNIFIL is authorised to implement the mandate under Chapter VII, would UNIFIL be successful?

UNIFIL is the only UN peace operation (also often called peacekeeping) where peacekeepers from three developed western nations, France, Spain and Italy, contribute with their soldiers as armed contingents after the 2006 war. So much so that these contingents are equipped with heavy armaments, including main battle tanks and artillery guns (an exception in UN peace operations). Being under Chapter VI mandate, UNIFIL can use such armaments only to defend itself and in defence of the mandate. Defending the mandate might mean the use of force against violations of SCR 1701, regardless of who violates it. It was predictable that a conflict between the IDF and Hezbollah would be vicious, and hence it justified such a well-equipped, robust force. Until the recent conflict between the IDF and Hezbollah, the author was under the impression that a robust peace operation like UNIFIL would be able to stand up to any threat from the IDF or Hezbollah when they are engaged in a full fledged conflict. Besides the mission’s inbuilt capability, the presence of peacekeepers from western nations will be a political deterrent to a major conflict in South Lebanon. The author’s assumption was proved wrong, and UNIFIL was forced into the bunkers by the IDF. It is more because the troop contributing countries did not want to risk the lives of their peacekeepers and less for anything else.

A Chapter VII mandate implies forcefully implementing it. Enforcing the mandate will have its consequences, and UNIFIL is neither capable of taking on the IDF and Hezbollah nor has the will of the troop-contributing countries to bear the costs. Therefore, a Chapter VII mandate will be a trap forcing UNIFIL to write its own obituary.

What would be the fate of UNIFIL then?

No matter the next mandate, the strength of UNIFIL will have to be reduced. The current peacekeeping budget stands at 5.6 billion USD. The combined budget for peace operations in the DRC, South Sudan, Central Africa, Lebanon and Abyei works out to approximately 620 million USD. If the US follow through on its threat to withdraw its contribution of 1.4 billion USD, the UN will have to implement drastic austerity measures if the international community wants to continue with peacekeeping.

The absence of a conflict between Lebanon and Israel after the 2006 war until now was primarily due to two reasons. Neither Israel nor Lebanon (Hezbollah) wanted a major conflict. Aside, the liaison and coordination mechanism of UNIFIL was effective in controlling the smaller triggers of conflict. UNIFIL was good at it. Notwithstanding the contention of Mizrahi and Levanoni, the US and Israel want UNIFIL to continue to secure South Lebanon on their behalf. What would be the fate of UNIFIL then? This is a time, the contours of Middle East peace are dictated by the US and Israel. With IDF continuing to occupy five Lebanese positions north of the Blue Line and its drones swarming over UNIFIL positions daily, the idea respect for state sovereignty, enshrined in the UN Charter, which is often associated with the Peace of Westphalia (1648), is not relevant anymore.

For the time being, neither the US nor Israel want UNIFIL to go away but wants the mission to clean the area south of the Litani River free of Hezbollah. With Hezbollah sweeping the South Lebanon’s municipal elections, it is a task nearly impossible. As it is, there are reports of the denial of freedom of movement to UNIFIL in its area of operations daily basis. As Hezbollah and its supporters slowly return to South Lebanon, the population probably does want UNIFIL to cross the red line and find Hezbollah’s remaining armaments.

UNIFIL's role is likely to get more complicated because of the ongoing conflict between Israel and Iran and the complex connection between Hezbollah and Iran. Although Iran didn't directly support Hezbollah in its conflict with Israel in 2024, the relationship remains strong. The Israeli strike on Iran on 13 Jun 2025 (which continues at the time of writing this), is likely to drag the region into a wider conflict with direct repercussions in Lebanon. While the Lebanese government and Hezbollah have shown restraint, the risk of opportunistic fringe groups exploiting the situation cannot be ruled out. This could lead to further Israeli attacks, potentially rallying Lebanese public support behind Hezbollah. The situation is volatile, and UNIFIL's path forward will require careful navigation to prevent escalation and maintain stability in the region. After the ceasefire, the LAF appeared to have had a better grip on South Lebanon. However, to exercise its authority fully as mandated by SCR 1701, it needs external support to build its capability. The effective liaison and coordination mechanism of UNIFIL, which has matured in the past few decades, makes it better positioned to support the capability-building efforts of the LAF.

It is time UNIFIL adapted to the need for a new approach to peacekeeping and contributes to conflict management with a smaller and leaner force. An unarmed observer mission equipped with the ability to look deep inside, respond rapidly to emerging situations that can trigger a major conflict and be the impartial peace broker will help UNIFIL do what it is best at. However, if the member states are not comfortable with unarmed peacekeepers, the mission could be lightly armed, even though it is difficult to fathom how the armed peacekeepers can defend themselves in another round of conflict between Hezbollah and the IDF. The model the author recommended while exploring the feasibility of a peacekeeping role in Ukraine can be explored for Lebanon as well. Some important factors that must be considered if the UNIFIL mandate is approved by the UNSC are:

• The mandate should be simple without any ambiguity in the wording. It must

include nothing other than observation, reporting, mediation by liaison, and

coordination, and help LAF to build its capability.

• Peacekeeping missions are legitimate once consented to by the host nations

and approved by the UNSC. But it does not have local legitimacy and

credibility. It must be earned by producing evidence daily basis. Once there is

local acceptance, there will be trust and cooperation. Therefore, there is a

need to enquire what the local population want.

• Peacekeepers must be sensitive to the local culture and not perceived as

intrusive. One can learn history by reading. But to understand culture, it needs

more than intellectual comprehension. Culture is felt and not learned by

reading.

• Nominating the Head of the Mission based on his ability to reflect the above

thoughts and not based on political considerations will help the mission to find

better acceptance at operational and tactical levels.

Major General (Dr) A. K. Bardalai (Retd) is a former peacekeeper and currently a Distinguished Fellow of the United Services Institute of India. He holds a PhD in UN Peace Operations from The Tilburg University, the Netherlands.