Abstract

Mandates of the UN peace operations differ in different situations, contexts, and missions. The protection of civilians has now become an essential part of these mandates. Even without explicit inclusion in the mandate, it is the peacekeepers’ moral responsibility to protect innocent civilians from life-threatening consequences. Despite several policy documents issued by the UN and using the Chapter vii mission mandate, the protection has remained a huge challenge for several reasons. These could vary from a hesitation to use force, a dictate from the home country or even a contingent’s desire to avoid future hostilities with a contesting group. This adversely impacts the UN peace operations’ performance and creates a negative perception of the UN’s ability to protect civilians. Even though military force has been used in many places to carry out the UN mandate, specific instances of such use to protect civilians have given mixed results. This paper examines if there is any tangible value in authorising UN peace operations to use force in protecting civilians in armed conflicts. An evaluation of the use of force for carrying out the mandate and specifically for the protection of civilians has been attempted. It proceeds first to ascertain the reasons for such authorisation and successful usage and looks at peacekeepers’ reluctance to use force. This has been followed up by examining a few cases of the use of force at operational and tactical levels and deducing that using force to protect civilians can be the right decision.

Keywords

principles of UN peace operations – mandate – protection of civilians – use of force –

International Humanitarian Law – caveats

1. Introduction

Despite their 75-year history, UN peace operations have recently come under increasing criticism for their inability to carry out the assigned mandate. The UN, in general and peace operations, in particular, are facing some fundamental challenges. The UN Secretary-General has underlined this in his report on the performance of UN peace operations.2 The UN’s inability to end the Ukraine and Gaza wars has severely damaged its image as an impartial peace broker. To make matters worse, the peace operations mission in Mali was forced to wind up due to the withdrawal of consent, and the Democratic Republic of Congo (drc) has asked the peace operations mission (monusco) to accelerate the phased withdrawal.3 The actions of Mali and drc have raised the question of the fate of civilians of a state that is in the middle of a conflict and whose security sector is unable to protect its population. Protecting civilians from the threat from armed groups in Mali or elements like M234 in eastern drc in the absence of a peace operations mission or host state’s enhanced capability will continue to be a bigger global challenge.5

The local population considers the peacekeepers the angels of peace and expects them to save their lives from violence regardless of the mission’s mandate. In one incident on 25 June 2022, the local population in eastern drc attacked the UN camp because they perceived the UN as incapable of protecting them.6 Similar incidents have been reported in the South Sudan and Central African Republic areas. As Trithart observed, local perception is a barometer of success for missions mandated to protect civilians. When the locals start to feel that a mission is incapable, they perceive it to be illegitimate or lacking local legitimacy, thus unlikely to cooperate.7 It is not important whether such perception is true or engineered. What is important is that the host states use the lack of local legitimacy as an excuse to ask the mission to exit.8

The UN peacekeepers have previously used force to implement their mandate. This was done in many UN peace operations from Congo in the 1960s, Somalia, Sierra Leone and even in Cambodia. Using force, however, has consequences, and an incident in Somalia is worth mentioning. It followed the catastrophic event of June 1993 in which 24 Pakistani troops of UN Operation in Somalia (unosom ii) were killed and 56 injured while trying to inspect a Somali national radio station and weapon storage site belonging to General Muhammed Aideed, the main leader of the Somali National Alliance (sna). In retaliation, on 12 July 1993, more than half a dozen Cobra helicopters of the US quick reaction force (deployed in support but not part of unosom) attacked the Somali peace meeting, first by tow missiles, and then by 20 mm cannon guns, which resulted in the death of many civilians including women and children. It was the Bloody Monday and, to Somalis, an act of war. The attack ended the remaining hope for salvaging peace.9 As reported by Peterson, who was reporting from the front lines in Africa for London’s Daily Telegraph, the Somalis wanted peace, and a peace agreement could have been achieved.10 The raid led many Mogadishu residents to join the growing insurgency against unosom ii, and the following month, the sna began deliberately targeting US forces for the first time. In response, on 3 October 1993, U.S. forces planned to seize two of Aidid’s top lieutenants during a meeting deep in the city. However, things did not go as planned as the raid led to the estimated death of 500 Somali civilians, around 1000 wounded, the deaths of 18 US soldiers (Rangers and Delta Force), over 70 wounded, and one soldier was dragged through the streets of Mogadishu. This was the turning point for the peacekeeping mission in Somalia.11 Therefore, the question arises whether there is an advantage in empowering peace operations to use force exclusively to protect civilians and whether such a provision in the mandate saves lives.

The paper examines the protection mandate and use of force, relates it to the principles of peace operations, and discusses reluctance to use force and its use in fulfilling the mandate in some previous UN peace operations missions. To contextualize the issue, it analyses the factors that inhibit the use of force and explores ways in which UN peace operations can be more effectively empowered to fulfil their mandates. The final section carries out an evaluation of the use of force for carrying out the mandate and specifically for the protection of civilians (PoC). The final section also attempts to ascertain its utility with examples from a few past and ongoing peace operations.

2. The Protection Mandate and Use of Force

International Humanitarian Laws explicitly state that ‘Any person who is not or is no longer directly participating in hostilities or other acts of violence shall be considered a civilian unless he or she is a member of armed forces or groups.’ Even in case of a doubt, he or she will be considered a civilian.12 The UN Charter provides for three chapters under which most of the UN peace operations are established. While Chapter vi looks at a pacific settlement of disputes, Chapter vii authorises the use of force to fulfil a mission mandate. On the other hand, Chapter viii (Article 52 and 53) deals with “Regional Arrangements” and encourages regional organisations to take ownership of peacekeeping operations in their respective regions with the approval of the Security Council. UN operation in Congo (onuc) in 1960 was specifically authorised to help maintain law and order in the Republic of Congo. UN Security Council Resolution (unscr) 143 and S/4387 called on Belgium to withdraw its troops and authorized the UN Secretary-General to provide the Congolese government with military assistance. The force was used to prevent Katanga province from secession from the country and succeeded in maintaining the integrity of Congo, though at a heavy toll on the peacekeepers. As against this, the mandate of unscr 814 (1993) on Somalia was to aid in relief provision and economic rehabilitation, foster political reconciliation, and re-establish political and civil administration. The UN Assistance Mission for Rwanda (unamir) established under unscr 872 (1993)13 was the first mission with a mandate to contribute to the security and protection of displaced persons, refugees, and civilians in Rwanda. However, the UN Mission in Sierra Leone (unamsil) in 2000 was the first mission that explicitly authorised the proactive use of force to protect civilians under imminent threat of physical violence.14 It was the time when the UN and world community were engaging in PoC as one of the essential components of UN peace operations. As the UN Policy of PoC states, “The PoC mandate in UN peace operations is grounded in international law, including international humanitarian law, international human rights law and international refugee law, and reflects the desire of the Security Council to protect civilians from harm.”15 Hence, the inclusion of the protection mandate provides legal authority as well as obligations to the peacekeepers. Post Brahimi’s recommendations, when the mandates became stronger and more capable, peacekeepers began to participate in complex missions. During this phase from 2000 to 2014, PoC was made a common part of the mandate in Mali, Central Africa, drc and South Sudan missions. This heightened international expectations, resulting in subsequent disappointment when the missions were unable to protect the civilians as expected.16

It is not only the military peacekeeper who fulfils the primary objective of the UN as regards the PoC or UN mandate, but every UN employee in a mission area plays an important role. UN and non-UN Civilian staff can prevent and mitigate violence by engaging and supporting institutional reforms, and the UN Police (unpol) contributes to the protection strategy by engaging with the community.17 PoC can be active and passive, such as providing shelters to fleeing civilians, proactive patrolling in the known trouble spots or rapidly responding to spots where trouble is likely to come up (based on actionable intelligence inputs) to deter the potential perpetrators are some such measures. Even rendering life-saving assistance to civilians marooned in floods (South Sudan) or helping them to escape volcanic eruptions (eastern Congo) can be termed as PoC. Intergroup or ethnic violence can bring untold miseries to the locals who are caught in the crossfire. M23 or cndp raids in eastern Congo, ethnic clashes between Dinka and Nuer – two prominent factions in South Sudan or civilians caught between the clashes of various clans’ groups of Somalia and even Sudan require the UN to use force to save them from being harmed. The stabilisation mission in Mali (minusma) witnessed many peacekeepers becoming casualties in their attempt to fulfil the UN mandate. Many troop-contributing countries (tcc s) had earlier too questioned sending their peacekeepers in harm’s way, be it in Somalia, Bosnia, Sierra Leone, Mali, or Congo.

A protection mandate becomes a necessity when a host state is unable to protect or is complicit in the crimes against its citizens. In the absence of any viable alternatives, civilians become the target of violence. A Human Rights Report stated that since 2023, widespread killings, rapes and looting of villages by Islamist armed groups forced thousands of people to flee at a time when the Malian junta asked the UN to wind up minusma by the end of 2023.18 Because of the lack of stabilisation mechanisms and the deadlocked peace process between the Mali Government and Cadre stratégique permanent, or csp, prospects for de-escalation in northern Mali appear to be very slim, and civilians continue to be the targets of all factions.19 As Mali and Somalia had demonstrated, following an active protection strategy makes the peacekeepers more vulnerable to retaliation by armed groups, one of the likely reasons for the reluctance of peacekeepers to resist the use of force.

3. Plausible Reasons for Reluctance to Use Force

Using force has many unintended consequences on the ongoing peace operations, cooperation with the factions, and safety of the peacekeepers. It may also lead to an increase in force protection measures, thus leaving the local population more vulnerable. The three UN peace operations where the use of force was made despite the UN being initially reluctant at the strategic levels were Congo in 1960–64, Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1992–95 and Somalia in 1993–95. All three resulted in traumatic experiences for the UN.20 After the Cold War and at the end of the traditional peace operations phase, the UN was called for multifunctional operations integrated with peacebuilding and the development of a just society. UN peace operations had practised containment and de-escalation, but under the new mandates, they were mandated to seek lasting resolutions as an end state. This expanded form was also loaded with exclusive Priority-One tasks of PoC, as in the case of four multi-functional missions in Mali, Central African Republic, South Sudan, and drc.

This expanded mandate presented a dilemma to the tcc s, who were reluctant to let their peacekeepers use force in such circumstances. It was due to the perception that the host state, which has the prime responsibility to protect its citizens, was complicit in crimes against its citizens; the tcc s did not want to compromise their strategic interest in the region or that country. More importantly, no member states like to see the body bags of their soldiers coming home because it becomes politically difficult to justify such sacrifices while attempting to bring peace to another country. Principles of peace operations, mandate interpretation, ambiguous PoC policy, inadequate resources, and the presence of national caveats are a few of the many reasons advanced as the reasons for reluctance to use force to carry out PoC.

3.1. PoC and Principle of Peace Operations

Consent is the first principle of a peace operation, as the effectiveness of PoC depends on the consent of the host state or the parties to the conflict. But consent is never absolute; it always comes with conditions that may never be spelt out in writing, and it would never be available at all levels. Consent at the strategic level is when a host state agrees to the deployment of a UN peace operations mission but may differ from consent at the operational/tactical level. Consent at the tactical level will be influenced by several other factors, such as the local legitimacy, the peacekeepers following the UN norms, how the local population perceives the mission, etc.21

At the time of identifying the principles of peace operations after the end of the Suez Crisis in 1956, consent was identified as the fundamental principle in the context of inter-state conflict. The drafters of the principles would not have thought of the necessity to apply this principle in case of intra-state conflicts, which grew in increasing numbers after the end of the Cold War. Peace operations were a tool for conflict prevention, management, and resolution. Peacekeepers were intended to be enablers rather than enforcers. They have no enemies and are not there to win any war. Given the vicious violence in the intra-state conflicts, the definition of consent at the operational/tactical levels has changed or has become ambiguous, leaving more scope for varying interpretations. Accordingly, peacekeepers who are required to operate in an ambiguous environment are at times forced to extract consent under coercion to ensure their freedom of movement and implementation of the mandate. Consent is withdrawn whenever the conditions change when acting against perpetrators of violence (that may be a party to the agreement) to protect civilians. Even at the strategic levels, consent could be given reluctantly, either under intimidation or in exchange for something that might be useful for the survival of the government in place.

When the host state withdraws consent at the tactical level without withdrawing it at the strategic level, the mission becomes untenable. The UN Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea (unmee) was established to solve boundary disputes between the two countries. However, when Ethiopia did not respect the verdict of the boundary commission, Eritrea withdrew consent at the tactical level without withdrawing consent at the strategic level. It allowed the mission to continue but obstructed the mission’s freedom of movement under the pretext of security reasons, making it very difficult for the UN to sustain the mission. Finally, the mission had to be closed on 31 July 2008.22 Conversely, even after the withdrawal of consent by the Khmer Rouge faction before elections in Cambodia in 1992 (untac), the UN authorities went ahead with the elections and fulfilled their mandate amidst sporadic firefights with the faction. In intra state conflicts, there are times when some elements of a host state might be complicit in the crimes against civilians (Bosnia or Rwanda or South Sudan). In such cases, consent becomes precarious, and any action against the host state might end up withdrawing its consent or drawing the UN Forces into a direct fight. In July 2016, when the government soldiers of South Sudan stormed the Terrain Hotel, which housed most international civilian employees and used violence against them, the UN Mission in South Sudan (unmiss) was found wanting. It was because the nearest unmiss contingent did not respond to the call for help, probably out of fear of the withdrawal of consent by the government of South Sudan.23 Apart from not acting, UN peace operations missions end up enabling the autocracy of the post-conflict authoritarian regimes.24

Impartiality is the second principle, and its notion is based on the availability of consent from all parties to the conflict. However, when the civilians are protected from one or more parties to the conflict, the protectors would be looked at as partial by these parties. The UN stabilisation mission in the drc (monusco) is in support of the host government and ended up targeting non state actors in support of the host state. This has been perceived as partial to the host state by the targeted parties, and the UN has been considered a faction in support of the host state and an easy target for M23 or other groups.25 It is an ethical dilemma, especially when acting against a host state, because of the inherent danger of withdrawal of consent.

Using minimum force is the third principle, and its definition is ambiguous in its phraseology.26 The conceptual thinking on using force always varies despite the clear division between Chapter vi and Chapter vii. During the peace operations in Suez and later Gaza (First United Nations Emergency Force – unef), the use of force was limited to self-defence.27 As per Sir Brian Urquhart, former UN Under-Secretary-General for Special Political Tasks: ‘The real strength of a peace operations force lies not in its capacity to use force, but precisely in its not using force and thereby remaining above the conflict and preserving its unique position and prestige.’28 However, from the time of the Second unef in 1973, the term ‘self-defence’ included forceful means to fulfil its duties under the mandate of the Security Council. The Agenda for Peace of 1992, followed by the Brahimi Report and the High-Level Independent Panel on Peace Operations (hippo) report of 2015, brought more clarity to the thinking on using force.29 The Cruz Report has been strongest in its opinion about the use of force.30

Despite a strong resolve that there should not be any reluctance to use force to protect civilians, there is still some hesitation even when it is justified because of its inherent ambiguity. General Rupert Smith, the UN Force Commander in Bosnia, felt that the application of force should aim to alter the decision-makers’ minds. As per him, the use of force at the tactical level to save civilians brings only tactical and temporary results unless it is applied to alter the minds of the decision-makers.31 There were situations in Bosnia when, on one hand, the tactical commanders took the risk to protect civilians. On the other hand, senior mission leaders did not call nato airstrikes against the Serbs who attacked Srebrenica, killed thousands of innocent Bosnian Muslims, and took Dutch peacekeepers hostage in July 1995.32 Such ambiguity becomes a restraining factor for unpol as well. For example, ‘using all necessary means’ can be confusing since unpol does not have the executive mandate to arrest and detain. Citing the example of Mali, Hunt reported that there were occasions when unpol, by following the Directive on Use of Force (duf), did not disarm armed militants who were threatening civilians because of a lack of executive mandate. Such differentiators are of no importance to the locals under threat.33

3.2. Mandate Interpretation

Another related topic connected to the principles of peace operations is the ambiguous wording of the mandate. Even when deployed under Chapter vii, the wording of the mandate creates ambiguity for the tcc s to interpret it, and many tcc s will use it as it suits them. The mandate of minusma, as approved by the unscr 2100, was under Chapter vii. However, it also uses wordings like “Reaffirming the basic principles of peace operations, including consent of the parties, impartiality, and non-use of force, except in self-defence and defence of the Mandate … .’ It further goes on to state that terrorism can only be defeated by a sustained and comprehensive approach. At the same time, the resolution, which is under Chapter vii, tasks the mission to protect civilians under imminent threat. The conflict between Chapter vii tasks and the need to adhere to principles of peace operations creates avoidable confusion in the minds of those tcc s who are not comfortable with using force against armed groups. Such tcc s use such ambiguity as an excuse to justify their inaction.34

The PoC concept has been contested even 25 years after the first PoC mandate, which was given to the UN peace operation in Sierra Leone (unamsil) in 1999. The PoC component of a UN mandate consists of all measures, from the robust use of force to peaceful communication campaigns. PoC has slowly become an agenda that authorizes the use of force, alongside ‘comprehensive whole-of-mission activities.’ There is still a debate on “to what extent pre emptive or proactive force is authorised or expected, and if the use of force is at all obligatory.” There are no clear pathways to use force for PoC and to deter future violence. Mandate language needs to be consistent. The text of a PoC mandate differs largely from one mission to another. The PoC sections of mandates for monusco (drc), minusma (Mali), minusca (Central African Republic) and unmiss (South Sudan) reveal these differences. As per the unmiss PoC mandate, the primary responsibility to protect civilians does not rest with the South Sudanese government. The most recent mandate for monusco states that several provinces would be the primary focus “whilst retaining a capacity to intervene elsewhere in case of major deterioration of the situation.”35

3.3. Ambiguous PoC Policy

The UN’s Report of the Special Committee on Peacekeeping Operations reaffirmed the importance of the PoC as the key objective of the UN peace operations.36 The latest UN policy of 2023 has reemphasised the three-tier action in the operational concept of PoC (Tier i: Protection through dialogue and engagement; Tier ii: Provision of physical protection, and Tier iii: Establishment of a protective environment), which was given in the policy of 2019.37 Bode and Karlsrud observed in the policy of 2019 that those who implement the concept have a different understanding of the norm. Hence, it is challenging to practise this concept.38 Even though the 2023 report is exhaustive and more detailed than the previous ones, their observation that the peacekeepers may have a different understanding of the norm may still hold good for some. For example, one of the guiding principles of the PoC mandate is that the protection of civilians must be fully consonant with the three principles of peace operations. Where there is ambiguity in the understanding of the principles of peace operations, some of the guidelines in the new policy also become ambiguous. Even the UN’s New Agenda for Protection, which took years to come out, gives out only guidelines. Nothing is mentioned about how to operationalise the PoC mandate.39

3.4. Inadequate Resources

To be able to prevent violence against civilians in an active conflict zone, the contingents on the ground must have real-time information, be able to analyse it and anticipate the likely attack on the civilians, and then only will be able to deploy rapidly in the affected areas. This tactical-level capability is still absent in most of the missions. For instance, when the Kiwanja massacre took place in the drc on 4–5 November 2008, the peace operations mission could not respond appropriately. The contingent responsible for manning the UN base had no interpreter, no advance information, an acute shortage of men and equipment and was in the middle of the periodical rotation.40 When the density of peacekeepers is thin, the strategy of deterrence by the threat to use force or the strategy of pre-emption (for example, patrolling in vulnerable areas) to provide passive protection is bound to fail.41 The problem of inadequate resources is further compounded because of the gravitational pull of over-emphasis on the PoC, creating a decision dilemma for the mission leaders.42 The story of the attack on the Indian peacekeepers’ outpost at Akobo on 19 December 2013 in South Sudan is also similar. Consequent to the killings of people of the Nuer tribe in South Sudan, as revenge, more than 3000 armed men of the Nuer tribe stormed the Indian outpost and killed 46 civilians of Dinka, who were sheltered at the post. Two warrant officers of the Indian contingents tried to intervene but were also shot dead at point-blank range. The Indian peacekeepers were badly outnumbered but still saved hundreds of other civilians. Instead of continuing with the firefight, the crisis was resolved at the political level by unmiss hq s by engaging the top leader of the Nuer tribe.43 As mentioned earlier, the application of force must be able to alter the decision-maker’s mind. In the instant case, the use of force would have resulted in just the opposite.

3.5. National Caveats

There is no peace operations force directly under the command of the UN hq s. Interestingly, there was a proposal to create a standing UN force during the time of drafting the UN Charter. The US, which does not contribute troops to UN peace operations, had volunteered to contribute 40,000 soldiers to such a force. The proposal never saw daylight due to the rivalry between the superpowers.44 Hence, the hq s are forced to fall back on the member states to contribute their troops for the peace operations that the UN Security Council has approved. Therefore, the performance of the peace operations contingents largely remains hostage to the tcc s. It has become the norm for the tcc s to establish their parallel command and communication channels to regularly monitor their contingents’ operations. A company of a different nationality under the command of an Indian contingent in Cambodia handed over their weapons to the Khmer Rouge. Similarly, even the uniforms were taken by the renegade militants from another company from a different nationality in Somalia (placed under the command of the Indian Brigade). tcc s also issue caveats like these to avoid risking their peacekeepers’ lives or not agreeing to operational deployment and redeployment in difficult areas. This was the opinion of Gen Romeo Dallaire, the then Force Commander of unamir during the Rwandan genocide.45

To some extent, even the unhq is known to have restrained the peace operations mission from using force against the perpetrators of violence. For instance, in Rwanda, New York was not only insensitive but passed explicit instructions to General Dallaire not to take any action against the genocidal Hutus. In Sierra Leone, there was tremendous reluctance to use force at the UN hq level to free the peacekeepers taken hostage. This trend, however, has changed for good. The national caveats come in the way of the operational flexibility of the commanders on the ground.46 As reported in the Economist, “The caveat system, and the broader aversion to risk from which it has arisen, leads to tragic inaction or, at the least, sluggish responses.”47 On the contrary, the performance of the peace operations contingents, whose governments either don’t interfere or do very little, have been par excellent worth emulation by other contingents.

The account of Colonel Edward Carpenter, a retired US marine (who served in unmiss as an operational staff officer from May 2019 until June 2020) about the laudable performance of Rwandan, Ghanian and Mongolian contingents supports the argument that those military contingents that were not restrained by their home governments took risks to protect civilians from armed rebel groups. Carpenter’s views on the national caveats working against effective peace operations were reinforced by the feedback from the Indian peacekeepers who have returned after their end of the tour of duty in unifil. Out of 237 total respondents, 57 strongly agreed and 123 agreed that the presence of national caveats is an excuse by some contingents not to use force when necessary.48

Carpenter also recalled one of his encounters with David Shearer, the Head of the Mission of unmiss, on 24 February 2020. On the suggestion that the mission was expected to do more to protect civilians regardless of how they suffer, the Head of the Mission remarked, “Most of those people were killed in inter-communal violence, which isn’t our job to prevent.”49 Mindsets of risk-averse mission leaders like Shearer, who has more faith in private military contractors than peacekeepers, are as demotivating as the national caveats that dwell heavily on the peacekeepers.50

4. Use of Force for the PoC at Operational and Tactical Levels

The application of force to protect civilians has evolved from the ‘use of minimum force’ under Chapter vi to the use of ‘all necessary means’ under Chapter vii. Using force for protection also means creating a condition to prevent the recurrence of conflict that endangers civilians and neutralising the elements that can endanger the civilians. Despite the reservations on the part of the member states and the peacekeepers in using force, there are several past and present instances of using force by the missions at the operational level and by the peace operations contingents at the tactical level. Some of the cases in the use of force for PoC provide useful deductions.

The October 2010 election in Cote d’Ivoire was certified by the srsg of the UN Operation in Cote d’Ivoire (unoci), which annoyed sitting and losing President Gbagbo. He refused to relinquish his power, resulting in a fight between the rebel groups and Gbagbo’s loyalists. unoci was also harassed and attacked by the loyalist forces. The loyalist forces shelled even the civilian population. Finally, authorised by the unscr 1975 of 30 March 2011, unoci, along with the French Lincorne force, used attack helicopters to attack and bomb the Presidential palace on 4 April 2011, defeated the loyalist force and took Gbagbo into custody. unscr 1975 was a civilian protection mandate with the authority to use all necessary means to prevent the use of heavy weapons against the civilian population. However, unoci received sharp criticism from Russia and mainstream media like bbc for excessive use of force and supporters of Gbagbo labelled unoci partial to Ouattara.51 That notwithstanding, the robust use of force helped to restore democracy and saved hundreds of civilians from danger. The use of force by the Force Intervention Brigade (fib) against M23 rebels in eastern drc in 2013 is another example of using force by the mission to protect civilians. However, the fib was successful only during its first year, after which it was like any other UN brigade with very limited effectiveness.

Rwanda, Bosnia, and Somalia are often quoted as examples of what peacekeepers could not do or failed to do. However, there were instances of forceful actions by commanders at tactical levels even before PoC became part of the mandate. In December 1993, a platoon of Norway contingent was heavily outnumbered by a Croatian battalion-sized force in Srebrenica. But it refused to hand over two Muslim nurses to the Croats for more than 12 hours. In another incident, when the tank detachment of the Norway contingent was lured into an ambush by the Bosnian Serbs, the crew opened the main guns of the tanks until the Bosnian Serb ambush team was silenced. Col Henricsson, the commanding officer, instead of taking clues from his political superiors, formulated his mission objective even if it became necessary to use force and ignore rules and regulations when the civilians were threatened. Ingesson has defined such resolve to achieve the mission objective, disregarding the highest political authority and without worrying for one’s future career as the culture of mission command, which takes decades to grow and develop.52

Major General MP Bhagat (the former Indian Brigade Commander in the peace operations mission in Somalia) recalled when the peacekeepers were forced to choose between the need for immediate military response or referring to the national governments when attacked by the armed rebel groups. One of the tasks of the Indian Brigade deployed in Somalia (unosom ii) was to protect the logistic convoy of the Irish Logistic Company, tasked to deliver humanitarian aid through a hostile area. In February 1994, the logistic vehicles came under heavy fire from the armed rebel groups. The leading protection vehicles of the Indian contingent turned back and engaged the rebel groups. In the ensuing gun battle, five Indian peacekeepers lost their lives, and three rebels were neutralised by the peacekeepers. The action of the brigade to use force without referring to the government of the tcc (India) could retrieve the logistic convoy from a dangerous situation.53 These examples of Bosnia and Somalia illustrate the challenges of peace operations when the tcc s tended to control the day-to-day functioning of their contingents.

In South Sudan, when an internal communal clash broke out in Malakal on 18 February 2014, UN peacekeepers, disregarding their safety, positioned themselves in between armed groups and prevailed to find a solution using means other than violence. Similarly, as narrated by one former staff officer (so) who served in the operational branch of unmiss on 7 September 2022, the White Army, one of the local militia groups attacked the internally displaced persons (idp) camp on the West Bank of the River Nile in the Upper Nile State of South Sudan. The UN (Indian) contingent in the area of operations of the idp camp was located approximately 150 km from the nearest post of unmiss and reacted quickly to deter the armed group from further attacking the camp with orders to use force in self-defence if necessary.54

There are many such examples of peacekeepers using force to protect civilians. What sadly comes to light is only the cases of failure to protect. It is because it is easier to market negative news than the truth. The truth, however, is that as observed by Walter, Howard and Fortna, despite the challenges with which UN peace operations missions are generally confronted, there is overwhelming evidence that UN peace operations significantly contribute to bringing peace by reducing civilian casualties and helping countries maintain post-conflict peace.55

5. Importance of Use of Force for PoC

Reasons for the failure to protect civilians cannot be solely attributed to UN peace operations. There are factors influencing the performance of peace operations such as inadequate resources, inhospitable terrain and vested political interests of the host states, which are beyond the control of either the UN or the UN peace operations mission. When capable peacekeepers, who are well-trained and well-equipped, are empowered and use force judiciously, the civilians in danger have a better chance of survival. At the operational level, effective use of force can help protect civilians from danger when provided with a resolute and able leadership.

Therefore, the centre of gravity of using force lies with the willingness of the member states, who, instead of issuing caveats, must encourage their peacekeepers to take the initiative to protect the civil population in danger. There are many examples of UN Forces using force and successfully protecting thousands of civilians in various missions. These must be taught and used as a symbol of UN actions. Otherwise, even though it is an unrealistic expectation of the local population for the peacekeepers to provide blanket protection irrespective of their capabilities, failing to protect will be a loss of hope for the ones who suffer the most in conflicts.56 It can be deduced that as of now, there is no better alternative to UN peace operations for the PoC in the intra-state conflicts to protect civilians in the face of the imminent threat to their lives.

6. Conclusion

This paper aimed to examine the value of authorising the use of force in UN peace operations. UN Peace Operations differ in different situations, contexts, and missions, but the PoC has now become an essential part of UN mandates. It is the peacekeepers’ moral responsibility to protect innocent civilians from life-threatening consequences. Despite several policy documents issued by the UN and using the Chapter vii mission mandate, the protection has remained a huge challenge for several reasons. As identified in the paper, these could be a lack of advanced information, inadequacy of force, a reluctance at the tactical level or a dictate from the home country. This adversely impacts the UN peace operations’ performance and creates a negative perception of the UN’s ability to protect civilians. Even though military force has been used in many places to carry out the UN mandate, specific instances of such use to protect civilians have given mixed results. This paper examined if there is any tangible value in authorising UN peace operations to use force in protecting civilians in armed conflicts. An evaluation of the use of force for carrying out the mandate and specifically for the protection of civilians has been attempted.

Notwithstanding the stronger mandates of authorising the use of force and use of all necessary means, UN peace operations have been repeatedly found wanting. Ambiguity in policies, inadequate strength of the peacekeepers, and absence of support from the unsc are some of the excuses often cited not to use force when failing to protect civilians. Besides, tcc s avoid consequent political fallout in their domestic constituency because of the possible casualties to their peacekeepers. Yet, there are examples of using force when the mission is led by strong and determined leadership. It is also observed that when tactical-level commanders disregard their safety and respond to the PoC, many lives have been saved.

To sum up, despite the setbacks and challenges, it will be reasonable to argue that there is still a sense of using force for the PoC in intra-state armed conflicts. One of the conditions to achieve this must be that the tcc s must refrain from interfering in the ongoing operations of a UN peace operation, and peacekeepers must stand up to the threat from the armed rebel groups, for which they are adequately trained. Because the UN peace operations can be as effective as the TCC S want them to be!

Biographical Notes

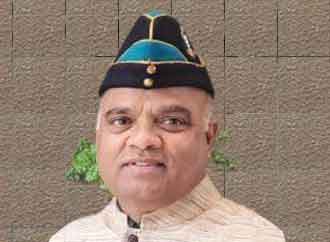

Major General (Dr) AK Bardalai, a veteran of the Indian Army, is an alumnus of the National Defence Academy and was commissioned into the Infantry on 11 June 1977. The general commanded an infantry division, was the Commandant of the Indian Military Training Team in Bhutan from October 2011 to January 2014, served in Angola in the early 1990s as an Unarmed UN Military Observer in the middle of the civil war and was the Deputy Head of the Mission and Deputy Force Commander of the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (unifil) from March 2008 to March 2010. The general was a member of the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (nupi) and Geneva Centre for Security Policy (gcsp) Study Team for the United Nations Truce Supervision Organisation (untso). The study report was presented to the unhq s on 31 May 2024. Post-retirement from active service, the general is pursuing his academic interests and remains engaged in activities related to UN Peace Operations. He holds a PhD in UN Peace Operations under the supervision of Prof. Dr. Joseph Soeters, Tilburg University, the Netherlands and Prof. Dr. Patricia M. Shields, Texas State University.

Foot Notes:

1.Major General AK Bardalai (retired) is a former peacekeeper and currently a Distinguished

Fellow of the United Services Institute of India. He holds a PhD in UN Peace Operations.

2.UN Security Council, ‘Overall Performance of UN Peace Operations Missions,’ Secretary

General Report, s/2023/646, 1 September 2023.

3.Daniel Forti, in his interview with srf News, 29 July 2023, For a copy of the letter

from drc to the UN, see .

4.M23 stands for Mouvement du 23 Mars – an abortive agreement signed between the drc

government and the Tutsi-led National Congress for the Defence of the People (cndp) on 23

March 2009. M23 rebels are breakaway soldiers of cndp based in the North Kivu Province

of drc.

5.Laurence Peter, ‘Mali Urges Immediate End to UN minusma Peace Operations Mission,’

bbc News, 17 June 2023, . Also see,

Sergey Sukhankin, ‘Wagner Suffers Another Military Setback in Africa, This Time in

Mali,’ Eurasia Daily Monitor, 31 July 2024, .

6.Al Jazeera News, 22 July 2022, ; ‘Rwanda, Congo and Uganda: The

Cursed Border,’ Information Brokers International, 3 February 2023, .

7.For more on local legitimacy, see Jeni Whelan, ‘The Local Legitimacy of Peacekeepers,’

Journal of Intervention and State Building, vol. 11, no. 3, 2017, p. 309, . Also, see Vanessa Frances Newby, Peace Operations in South Lebanon:

Credibility and Local Cooperation (New York: Syracuse, 2018), pp. 25–81.

8.Albert Trithart, ‘Local Perceptions of UN Peace Operations: a Look at the Data,’ ipi Issue

Brief, September 2023 .

9.James O. Tubbs, ‘Intervention in Somalia: unitaf and unosom ii,’ Beyond Gunboat

Diplomacy: Forceful Applications of Airpower in Peace Enforcement Operations (Air University

Press, 1997), and Alexander Cockburn, ‘Somalia

Slips from Hope to Quagmire: in Monday’s Attack the Peacekeepers Looked More Like

Warlords,’ Los Angeles Times, 13 July 1993. Also see James Lechner, With My Shield: an Army

Ranger in Somalia (New York: Osprey Publishing, 2023), pp. 141–242.

10.Scott Peterson, ‘Bloody Monday,’ Me against My Brother: at War in Somalia, Sudan

and Rwanda (New York/London: Routledge, 2000), pp. 117–136. tow missiles are Tube

Launched-Optically Tracked-Wireless Guided missiles.

11.Lise Morje Howard, UN Peacekeeping in Civil Wars (Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press, 2008), pp. 25–27; ‘The Mogadishu Mile: an Annual Tribute to Committed Excellence,’

.

12.‘International Humanitarian Law Data Base,’ icrc, .

13.UN, s/res/872 (1993), 5 October 1993.

14.UN, s/res/1289 (2000), 7 February 2000.

15. ‘Policy: The Protection of Civilians in United Nations Peace Operations,’ UN Department of Peace Operations, Ref.2023, 05, 1 May 2023.

16.UN General Assembly, Report of the Panel on United Nations Peace Operations, a/55/305-s/2000/809 (21 August 2000).

17.Allard Duursma, Corinne Bara, Nina Wilén, Sara Hellmüller, John Karlsrud, Kseniya

Oksamytna, Janek Bruker, Susanna Campbell, Salvator Cusimano, Marco Donati, Han

Dorussen, Dirk Druet, Valentin Geier, Marine Epiney, Valentin Geier, Linnéa Gelot,

Dennis Gyllensporre, Annick Hiensch, Lisa Hultman, Charles T. Hunt, Rajkumar Cheney

Krishnan, Patryk I. Labuda, Sascha Langenbach, Annika Hilding Norberg, Alexandra

Novosseloff, Daniel Oriesek, Emily Paddon Rhoads, Francesco Re, Jenna Russo, Melanie

Sauter, Hannah Smidt, Ueli Staeger & Andreas Wenger, ‘UN Peace operations at 75:

Achievements, Challenges, and Prospects,’ International Peace Operations, October 11, 2023,

doi: 10.1080/13533312.2023.2263178. Also see The UN Department of Peace Operations,

‘The Role of United Nations Police in Protection of Civilians,’ August 2017, .

18.Human Rights Watch, ‘Mali: Mounting Islamist Armed Group Killings, Rape: UN Peacekeepers’

Departure Complicates Efforts for Security; Provide Aid,’ 13 July 2023, .

19.International Crisis Group, ‘Northern Mali: a Conflict with No Victors’ (Jan 2025),

.

20.Trevor Findlay, ‘The Use of Force in UN Peace Operations,’ sipri (2002), p. 1; .

21.‘Host-Country Consent in UN Peace Operations: Bridging the Gap between Principle and Practice,’ Stimson, 8 September 2022,. Also see, Anjali

Dayal, ‘A Crisis of Consent in UN Peace Operations,’ ipi Global Observatory, 2 August 2022,

.

22.Patrick Cammaert and Andreas Sugar, ‘United Nations Mission in Ethiopia and Eretria

(unmee),’ in Joachim A. Koops, Norrie Macqueen, Thierry Tardy and Paul D. Williams

(eds.), The Oxford Handbook of United Nations Peace Operations (Oxford: Oxford University

Press, 2015), pp. 671–81.

23.Lauren Spink and Matt Wells, ‘Under Fire: the July 2016 Violence in Juba and UN Response,’

Centre for Civilians in Conflict, 5 October 2016, and ‘UN: Rape Used as a Tool for Ethnic Cleansing in South Sudan,’ cbs News, 2 December 2016, .

24.Sarah von Billerbech and Oisin Tansey, ‘Enabling Autocracy? Peacebuilding and Post-Conflict Authoritarianism in the Democratic Republic of Congo,’ European

Journal of International Relations, vol. 25 (3), 2019, pp. 698–722, .

25.UN Security Council, s/res/2666 (2022), 20 December 2022. For more details on

stabilisation, see Cedric de Coning, ‘Is Stabilization the New Normal? Implications of

Stabilization Mandates for the Use of Force in UN Peace Operations,’ in Peter Nadin (eds.),

The Use of Force in UN Peace Operations (1st ed.) (London: Routledge, 2018).

26.AK Bardalai, ‘UN Peace operations and Ambiguity in Normative UN Norms,’ Manohar

Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses Journal of Defence Studies, vol. 16, no. 3,

July–September 2022, pp. 3–31.

27.UN General Assembly, ‘Summary Study of the Experience Derived from the Establishment

and Operation of the Force,’ Report of the Secretary-General to the General Assembly,

A/3943, 9 October 1958.

28.Brian Urquhart, A Life in Peace and War (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1987), pp.

178–79.

29.UN General Assembly Security Council, Agenda for Peace, a/47/277 – s/24111 (17 June

1992); UN General Assembly, Report of the Panel on United Nations Peace Operations,

a/55/305-s/2000/809 (August 21, 2000); United Nations Peace Operations: Principles and

Guidelines (New York: UN Department of Peace Operations, 2008), p. 31 and High-Level

Independent Panel Report a/70/95–s/2015/446, 17 June 2015.

30.Lieutenant General (Retired) Carlos Alberto dos Santos Cruz, ‘Improving Security of

United Nations Peacekeepers: We Need to Change the Way We Are Doing Business,’ 19

December 2017, . Also see, Paul D. Williams, ‘Cruz Report: the Politics of Force and the United Nations Peace Operations Trilemma,’ 9 February 2018,

.

31.Rupert Smith, ‘Bosnia, Using Force amongst the People,’ The Utility of Force: the Art of War in the Modern World (England: Penguin, 2005).

32.Human Rights Watch, ‘The Fall of Srebrenica and the Failure of UN Peace Operations:Bosnia and Herzegovina,’ vol. 7, no. 13, October 1995; and Jett, ‘Why Peace Operations Fail,’

n. 7, pp. 15–18.

33.Charles T. Hunt, ‘To Serve and Protect: the Changing Roles of Police in the

Protection of Civilians in UN Peace Operations,’ Civil Wars, 21 September 2022, doi:

10.1080/13698249.2022.2119507.

34.UN Security Council, s/res/2100 (2013), 25 April 2013, and M Brosig, Cooperative Peace Operations in Africa: Exploiting Regime Complexity (London: Routledge, 2017), pp. 227–40.

35.Alexander Gilder, ‘The UN Force and Use of Mandates to Protect Civilians,’ Lieber Institute, 16

February 2023, .

36.UN General Assembly, Report of the Special Committee on Peace Operations, Official

Records Seventy-Fifth Session Supplement No 19 A/75/19, 15 February–12 March 2021.

37.UN, ‘Policy: the Protection of Civilians in United Nations Peace Operations,’ UN

Department of Peace Operations, Ref.2023.05, May 1, 2023. Also see ‘The Protection of

Civilians in United Nations Peace Operations,’ The UN Department of Peace Operations,

Ref. 2019.17, 1 November 2019.

38.Ingvild Bode and John Karlsurd, ‘Implementation in Practice: the Use of Force to Protect

Civilians in United Nations Peace Operations,’ European Journal of International Relations,

vol. 25, no. 2 (2019), pp. 458–485, doi:10.1177/1354066118796540. Also, see Alexander Gilder,

‘The Protection of Civilians in UN Peace Operations,’ Stabilization and Human Security in

UN Peace Operations, (New York: Routledge, 2022), pp. 26–33.

39.Damian Lilly and Jennifer Welsh, ‘The UN’s New Agenda for Protection: Can It Make a

Difference?’ipi Global Observatory, 13 May 2024, .

40.Z Mampilly, ‘Indian Peace Operations and Performance of the United Nations Mission

in the Democratic Republic of Congo,’ in T Tardy and M Wyss, (eds.), Peace Operations

in Africa: the Evolving Security Architecture (Routledge: New York, 2014), pp. 113–31 and ID

Quick, Follies in Fragile State: How International Stabilisation Failed in the Congo (London:

Double Loop, 2015), p. 127.

41.Stian Kjeksrud, ‘Utility of Force to Protect Civilians from Violence: Violence: Exploring Outcomes of United Nations Military Protection Operations in Africa (1999–2017),’ Civil

Wars,

42.Adam Day and Charles T. Hunt, ‘Distractions, Distortions, and Dilemmas: the Externalities

of Protecting Civilians in United Nations Peace Operations,’ Civil Wars (2021), doi:

10.1080/13698249.2022.1995680.

43.Major Sammer Pal Toor (member of the Indian contingent), Interview by the author.Also, see .

44.Paul D. Williams and Alex J. Bellamy, ‘Peace Operations during the Cold War,’ Understanding Peace Operations (Cambridge: Polity, 2021), p. 55.

45.Romeo Dallaire, Shake Hands with Devil (Cambridge: Random House, 2013) and hrw,‘Ignoring Genocide,’ .

46.Ibid.

47.Economist, 2021, ‘UN Peacekeeping Is Hamstrung by National Rules for Its Troops,’

.

48.AK Bardalai, United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon: Assessment and Way Forward

(Doctoral dissertation, The Tilburg University, 2021), .

49.Colonel Edward Carpenter (a US Marine who served in the unmiss operational

branch), Interview by the author. Also, see unmiss.unmissions.org and intellinews.com

50.David Shearer, ‘Privatizing Protection,’ Global Policy Forum. August/September 2001,

.

51.Guilia Piccolino, ‘The Dilemmas of State Consent in United Nations Peace Operations,’

in Thierry Tardy and Marco Wyss (eds.), Peace Operations in Africa: The Evolving Security

Architecture (Routledge: New York, 2014), pp. 227–44 and John Karlsrud and Ingvild

Magnaes Gjelsvik, ‘Protection of Civilians in the Absence of Peace Agreement: Darfur,

Chad/drc, and Cote d’Ivoire,’ in Cedric de Coning, Chiyuki Aoi and John Karlsrud (eds.),

UN Peace Operations Doctrine in a New Era (New York: Routledge, 2017), pp. 211–26.

52.Tony Ingression, ‘In the name of Peace,’ The Politics of Combat: the Political and Strategic

Impact of Tactical-Level Subcultures, 1939–1953 (Sweden: Lund University, 2016), pp. 231–55.

53.Major General Mono Bhagat (former Indian Brigade Commander in unsom ii), Interview

by the author, 4 August 2024.

54.One Indian military staff officer who served as an operational officer in unmiss at the

time of the incident, Interview by the author.

55.Barbara F. Walter, Lise Morje Howard, and Virginia Page Fortna, ‘The Extraordinary

Relationship between Peace Operations and Peace,’ British Journal of Political Science

(2020): 3, doi:10.1017/S000712342000023X. Also see Virginia Page Fortna, ‘Does Peace

Operations Keep Peace? International Intervention and the Duration of Peace after

Civil War,’ International Studies Quarterly, vol. 48, no. 2 (2004): pp. 269–292, .

56.Alan Doss, ‘Facing the Future: Actions for Peace,’ A Peacekeeper in Africa: Learning from

UN Interventions in Other People’s Wars (Colorado: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2020), pp.

292–93.

Major General (Dr) A. K. Bardalai (Retd) is a former peacekeeper and currently a Distinguished Fellow of the United Services Institute of India. He holds a PhD in UN Peace Operations from The Tilburg University, the Netherlands.